Destroy All Prisons Tomorrow

The weekend of August 19 2017, amid the second nationwide inside/outside mass protest against prison slavery in as many years, Jacobin Magazinepublished an article against prison abolition entitled How to End Mass Incarceration by Roger Lancaster. Lancaster argued that returning to an ideal of puritan discipline and rehabilitation is more realistic than pursuing the abolition of prison entirely.

This is an extremely bad article, it's treatment of pre-1960's USA is revisionist, dripping with white supremacy & American exceptionalism

— ghost (@Solidar) August 19, 2017

The history of reform has been a history of increased repression, growing prisons, and increased violence on marginalized communities

— J.B. Ware (@jaybeware) August 21, 2017

Jacobin caught a lot of deserved flack from abolitionists on social media for it. Numerous scholars, organizers and journalists decried Lancaster's article, creating such an online storm that Jacobin decided to publish a response article entitled What Abolitionists Do penned by Dan Berger, Mariame Kaba and David Stein. Unfortunately, this response fails to fully critique Lancaster's arguments and instead sells other abolitionists out. Their thesis paragraph reads:

Critics often dismiss prison abolition without a clear understanding of what it even is. Some on the Left, most recently Roger Lancaster in Jacobin, describe the goal of abolishing prisons as a fever-dream demand to destroy all prisons tomorrow. But Lancaster’s disregard for abolition appears based on a reading of a highly idiosyncratic and unrepresentative group of abolitionist thinkers and evinces little knowledge of decades of abolitionist organizing and its powerful impacts.

The Lancaster article levies the typical straw-man critique of abolition as an unrealistic “heaven-on-earth” vision. He presents Michel Foucault’s vision of a carceral society from Discipline and Punish as an alternative aspiration and argues that “we should strive not for pie-in-the-sky imaginings but for working models already achieved in Scandinavian and other social democracies.” He accuses abolitionists of being “innocent of history” and “far out on a limb” when comparing prison to chattel slavery.

These arguments expose a poverty of Lancaster’s analysis, and they are easily refuted. The idea that the US could adopt a Scandinavian style prison system through simple public awareness campaigns is desperately naive to the history of racial capitalism on this continent. The idea that a Foucauldian carceral society could exist here without massive quantities of racially targeted violence and coercion is far more pie-in-the-sky than the abolitionist recognition that prison depends on and cannot function without abominable levels of dehumanization and torture. Lancaster is the one with a utopian vision divorced from history, his prisons without torture or slavery can only be imaged by someone who hasn’t honestly grappled with the history of the US as a settler colonial nation that has always been existentially dependent on putting chains on Black people.

>Rather than confronting Lancaster directly on these points, Berger, Kaba and Stein dodge half the argument. They effectively inform an out-of-touch Lancaster about the practical works of abolitionists navigating reform as a means to our end, and the growing movement that those with abolitionist commitments and analysis have inspired. Unfortunately, they let the rest of his argument stand, transferring his straw man to a group of “highly idiosyncratic and unrepresentative... abolitionist thinkers” who Lancaster’s “reading seems to be based on”. This vague language begs a few questions: who are these thinkers that “demand to destroy all prisons tomorrow” and why can’t they be named? Why is their work excluded from Berger, Kaba and Stein’s understanding of “What Abolitionists Do”?

Neither of these articles managed to mention the August 19 Millions for Prisoners March, or last September’s nationally coordinated prison strike, an event that Jacobin stood out among left and even mainstream news sources in their failure to cover. Instead, Berger, Kaba and Stein focus almost all attention on a strategy of non-reformist reforms. They go in depth describing abolitionists winning victories similar to those Lancaster advocates.

These victories come from good and vital work that we have no desire to dismiss or undervalue. We honor and respect Critical Resistance, Incite! and the other mentioned organizations, and recognize that much of their vision and efforts are not limited to what was portrayed in this article. But we take exception to Berger, Kaba and Stein’s choice to position non-reformist reform as though it is or can be the whole of abolition, and their dismissal of other approaches as “highly idiosyncratic and unrepresentative”.

Both Lancaster’s article and the abolitionist's response reference efforts to abolish chattel slavery, but neither acknowledge the most important historical event from that time: the Civil War. The southern plantation system was not and could not have been converted into a humane system of rehabilitative discipline as Lancaster suggests, nor could it have been abolished by a steady campaign of “non-reformist” policy changes chipping at it. To suggest either response to the present system of mass incarceration and prison slavery is equally absurd, yet these are the only things being discussed in Jacobin.

The abolitionists of the 1800s certainly engaged in legislation and policy change, and their contemporaries certainly countered with visions of a kinder gentler plantation, but history was in fact made by those who engaged in acts that forced change on a nation unwilling to depart from its racist history. It was the underground railroad, the harboring of freed slaves, and the support for uprisings, sabotage and rebellions which compelled Lincoln to sign the emancipation proclamation. It took the bloodiest war in US history to enforce that proclamation. This discussion about “how to end mass incarceration” that does not include forcibly overcoming the violent persistence of white terror and black captivity in the united states is completely out of touch.

BRICK BY BRICK, WALL BY WALL, EVERY PRISONS GOT TO FALL!#A19 #EndPrisonSlavery #FreeThemAll #freepp #fightsupremacy #TearItDown pic.twitter.com/iDlUAvVNua

— Brandy (@Spacewoman333) August 19, 2017

As prison rebels reminded us on August 19, and continue to remind us every day, slavery did not end with the set of reforms that followed the Civil War. In fact, it was the compromises of policy-change oriented abolitionists that allowed the 13th Amendment to pass with an exception clause that leaves us still fighting to abolish slavery here today.

No progress against white supremacy in the United States has ever been made by reform alone. Before the civil war, non-reformist reforms of slavery were won amidst an uncompromising “fever-dream demand” to free all slaves now. That demand was eventually won because slave revolts and the underground railroad did not only dream it, they pursued and realized their demands through direct action. After the war, similar demands and actions were part of every step toward liberation and against convict leasing, Jim Crow, and the Ku Klux Klan. These demands and dreams remain part of the struggle against prison slavery, mass incarceration and white terrorism today. To dismiss them as “highly idiosyncratic and unrepresentative” is an insult.

It is naïve to think that ending prison won't require as much fight as every other concession wrenched out of the system of racial capitalism that founded America. That fight is already occurring, it's being led by the prisoners, and the pressure they exert is essential to the advance of any policy change or non-reformist reforms promoted by the article. It is incredibly disappointing to see the scholar-activist abolitionists who wrote this article distance themselves from prison rebellions, prisoner solidarity organizations, and the roots of the abolition movement.

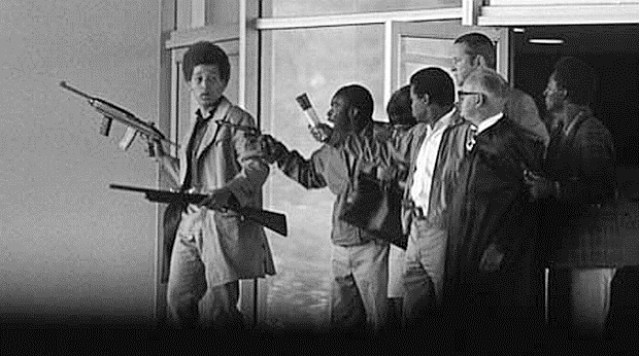

One of these authors, Dan Berger has made his career studying political prisoners and black liberation revolutionaries. He wrote The Struggle Within and Captive Nation, which draw from the rebellions of the 1970s. In this article he departs from the respect and honoring of black revolutionary intellectuals that characterize his other works. He's erased the fact that prison abolition was largely founded on George and Jonathan Jackson's deaths and their willingness to die rather than be incarcerated a single day longer. It is an egregious offense for this scholar of that history to now say “a fever-dream demand to destroy all prisons tomorrow.. [is] highly idiosyncratic and unrepresentative... [of] abolitionist organizing.”

Why is this happening? Why is Berger betraying his inspiring research subjects for Jacobin and Lancaster? What reason do these abolitionists have for reframing and excluding radicals and revolutionaries from abolitionism? It appears they'd like to convince Jacobin's readers that most abolitionists are respectable people whose vision is not so far from Lancaster's. They also seem keen to define abolition in a way that academics can comfortably adopt without risking career advancement. Then there’s the suspicious coincidence that they’ve limited abolition's tactical scope to approaches that center the work of the non-profit industrial complex and pandering politicians. We don’t like speculating about the potentially self-serving motives of our allies. We’d rather trust that Berger, Kaba and Stein focused their article on what they saw as the most tedious aspect of Lancaster’s tired argument. We trust, but not blindly.

The last paragraph of What Abolitionists Do recognizes the “urgent need for robust debate” and claims that the “debate must engage what exists in on-the-ground organizing”. We agree, which is why we believe the discussion must include prison rebels and the organizations that fight with them. Anarchist Black Cross Chapters, The Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee of the IWW, and various other groups are working to back up the prisoners who refuse to be slaves today, who won’t wait for some imagined non-reformist reformed future.

We and the prisoners we work with have coordinated the largest prison strikes and protests in history. According to estimates from Solidarity Research, our actions can cost prison systems hundreds of thousands of dollars per day. One anarchist prison rebel in Ohio did the math and concluded that a well supported prisoner strike would tank not only the prison system, but the entire state budget in a few weeks’ time. On August 18, when Lancaster's article came out, prison rebels and their supporters had frightened Florida and South Carolina into locking down their entire system for the weekend, costing them thousands of dollars, and significant public support. We are building power and pursuing abolition by making prison impossible, not merely by slowly reforming it out of existence.

Abolition now! is not just for “bumper stickers or social media” it is a call to action which is being answered, which is accumulating power, and which can mutually reinforce the work done on non-reformist reforms. The pressure of resistance can force reform concessions, which in turn can empower and embolden further resistance. This feedback loop can have great power to corrode the prison system and eventually topple it, and all the oppressive systems that depend upon it, but not if the non-reformist reformers are more interested in appealing to Lancaster’s disciplinary vision than in solidarity with prisoner resistance.

We support a diversity of tactics, and respect all the work Berger, Kaba and Stein do and hold up in their article. We recognize the need for creative alternatives as well as non-reformist reforms that give our incarcerated comrades, their families and the communities targeted by the prison system room to breathe and space to struggle more effectively. We respect the hell out of the work of the organizers, scholars and journalists who have helped win those reforms, but we also demand that the work and risks of prison rebels and outside solidarity efforts be recognized. We are abolitionists not only because we envision and are committed to building a new world, but also because people we love are trapped in these facilities that existentially depend on abominable practices of slavery and torture and that maintain an intolerable white supremacist social order for the rest of us. We won’t let those who resist from inside the walls, who demand freedom first and freedom now to be quietly swept into the shadows for the sake of easier arguments with abolitions opponents.